[Our Oddball Stocks Newsletter guest writer Catahoula (@CatahoulaValue, previously) writes in with thoughts about banks' results this earnings season.]

“At recent prices, bonds offer such low yields that an investor who buys them for their supposed safety is like a smoker who thinks he can protect himself against lung cancer by smoking low-tar cigarettes.” - Benjamin Graham, The Intelligent Investor

Back in business school, the term “Risk Free Return” signified what an investor could earn on an investment with zero risk. U.S. Treasury obligations were regarded as a proxy for “zero risk” pertaining to a “return of capital.” In other words, with a U.S. Treasury, you will get your money back at maturity in almost every conceivable circumstance. Therefore, there is no “credit risk.”

However, another key risk was left out altogether: Inflation leading to higher interest rates, or “market risk”. The Consumer Price Index (CPI) grew at an annualized 9% rate from 1972 to 1983, but inflation has remained largely dormant for the last four decades. After the U.S. gained an upper hand on inflation by the late-1980s, average inflation rate rocked along at ~2.2% average thereafter. Before the pandemic, from 2009 to 2019, the U.S. had an even smaller average inflation rate at just 1.8% annually.

Many bankers have never experienced this new kind of rising price environment. Inflation is a risk to bank bond portfolios, not only due to falling asset values from “market risk,” but what we see as an emerging threat: “liquidity risk.” If interest rates continue rising—and bonds continue falling—banks holding high quality bonds until maturity may not experience credit losses, as many intend to hold bonds to maturity. However, they are now experiencing sharply higher funding costs.

We are reviewing bank earnings releases in advance of our upcoming Issue 42 of the Oddball Stocks Newsletter, which will be published next month. Based on the last 40 years, everyone is especially attuned to credit. With good reason! In the book Ten Lessons Bankers Never Learn, Courtney Dufries says there are many things which can kill a bank, but in Lesson #7: “It’s almost always bad loans.”

Share prices at the largest U.S. money center banks have dropped considerably, making them a much better bargain, but is credit quality an issue? Any cracks? Elevated delinquencies? Adverse classifications? Nope! Although rate- and market-sensitive businesses (mortgage and investment banking) are weaker, this is a revenue problem, and is not credit-related. JPMorgan Chase and Bank of America are doing well. Citigroup posted fine results, but a major shift in strategy brings execution risk. Wells Fargo still has number of regulatory consent orders outstanding, including the $2 Trillion cap on assets.

Further down the asset-sized stack, there’s several mid-sized banks that boosted provision expenses, such as M&T Bank Corp (MTB) and Comerica (CMA), but not in a concerning fashion. We trust that MTB will get their arms around the People’s United Financial acquisition. CMA is well-managed and especially asset-sensitive, with any weakness cushioned by higher NIM and lower expense ratios.

One of the most interesting pre-announcements was Provident Bancorp (PVBC), which sees a “likely loss” for Q322. The holding company for BankProv announced that they are repossessing crypto-currency mining rigs in exchange for the forgiveness of a $28 million loan. However, the bank has not entered into an agreement for the resale of the collateral. Falling Bitcoin hits crypto mining revenue, while electricity costs are soaring. Thus, these rigs are not likely to fetch what they once would.

“Americans are getting stronger. Twenty years ago, it took two people to carry ten dollars’ worth of groceries. Today, a five-year-old can do it.” – Henny Youngman

Inflation is an invisible monster. Fixed income investments such as annuities, pensions and bonds suffer when the “cost of living” rises. At least stocks provide some opportunity to protect against the loss of purchasing power. In an inflationary environment, although operating expenses are higher, a company can boost its revenues accordingly, maintaining or even increasing profits. This in turn supports increases in dividends and, in turn, higher share prices.

But very few banks own equities. In the entire history of credit, there’s never been a bond issuer who has paid back more than was due. Many banks which stretched two-three years ago for longer duration bonds—even U.S. Treasuries and government-guaranteed Mortgage-Backed Securities—have bond portfolios which are starting to resemble “Return-Free Risk” rather than “Risk-Free Return”.

Why? Deposit costs are soaring! A short primer on Federal Funds: As customers deposit money at banks, those deposits provide them with funds required for extending loans to their customers. Federal Funds are excess reserves held by banks, over and above the regulatory reserve requirements of the Federal Reserve Bank. The current Federal Funds target rate is 3.00% to 3.25%, which is set as a range between an upper and lower limit, but the actual rate is set by the inter-bank lending market.

Banks borrow or lend their excess funds to each other on an overnight basis, since some banks have too many reserves and others have too little. This is an overnight loan, so banks maintain credit lines with many other institutions. If amounts are continually borrowed—credit lines are tapped out--counter-parties may get nervous and refuse to lend, even overnight. To balance its books, a bank is then forced to approach the Federal Reserve discount window, which is perceived as a lender of last resort.

Since Federal Funds are a large, short duration source of funds, they introduce significant stress to a bank balance sheet. Thus, banks typically try to stretch maturity of their liabilities with longer duration products. Enter the Certificate of Deposit. Even with Federal Funds in the low 3.00% range, banks are now offering 4.5% one-year CDs—the highest interest rates on CDs in years--through brokerage firms. But CDs can be volatile if too many leave at once.

The most stable funding source for banks is core deposits, which include demand deposit and savings accounts. “Demand deposits” seem counter intuitive as a stable funding source, because their designation implies that they can be gone in an instant, which they can. But many DDA accounts added together on a bank balance sheet are especially stable (unless the bank itself is in danger).

If the core deposits are in small retail accounts (which typically happens at money center banks), this is even better as a funding source because the bank doesn’t face the risk that several large depositors imperil its liquidity by walking away all at once.

We look at the current state of the industry: very few credit problems, with Federal Funds and other funding costs rising rapidly, as starting to resemble the late 1970s and early 1980s, when higher interest rates impaired the financial structure of savings and loans who had balance sheets composed of long-term assets and short-term liabilities.

Back then, regulators arranged mergers between failing thrifts and solvent ones (they often resembled “shotgun marriages”) to reduce the cost of resolution to the deposit insurance fund. In these mergers, the acquiring financial institution was allowed to employ the purchase accounting method, which had been rarely used in the thrift industry prior to 1980. Purchase accounting treats the difference between the purchase price and the fair market value of the acquired bank as “goodwill”.

Under Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP), “goodwill” was the amortized over its useful life, which could be up to a maximum of 40 years. For regulatory purposes, the full amount of goodwill created by mergers (“supervisory goodwill”) was counted as capital before the FIRREA was enacted in August 1989. Therefore, the purchase accounting method enabled solvent thrifts to acquire failing ones without raising capital.

Unfortunately, “goodwill” often had to be written off. Thrifts, emboldened with new capital, engaged in aggressive risk taking that ranged far afield from their traditional one-to-four family homes of a savings and loan. Large acquisition and development lot developments loans, speculative home construction, special use facilities such as water parks etc.—all caused large losses.

In the present day, higher long-term interest rates have caused unrealized bond losses on bank balance sheets if they are “marked to market”. You get different reactions from an accountant, regulator, or investor. If an accountant deems a bank to be a trader, they force the institution to immediately recognize bond losses as a hit to both the income statement and retained earnings. This is rare.

Otherwise, accountants treat unrealized losses lightly, providing two options under GAAP: “Held to Maturity” (HTM) and “Available for Sale” (AFS). Neither is recognized on the income statement. HTM merely shows up in the statement footnotes. AFS deducts losses as an adjustment both to asset values and to retained earnings through Accumulated Other Comprehensive Adjustment (AOCI).

The regulators acknowledge that bonds are scheduled to pay 100 cents on the dollar at maturity, unless

there’s a credit-related impairment. The unrealized gains and losses from interest rates converge towards zero as the bond maturity approaches. Therefore, regulators don’t consider bond portfolio market losses as a hit to regulatory capital--there’s no threat to solvency. No harm, no foul?

As an investor, if you take a similar view as an accountant or regulator, you should realize that “De Nile” is not just a river in Egypt. As a crypto meme recently wagged: “If I lost all the currency in my wallet, but I have the same amount of cash in my bank account, am I really in the hole at all?” Investors generally step past denial and realize that the bond market value losses are real.

Indeed, many banks which stretched for yield are starting to have AOCI losses represent a substantial part of their equity capital, and in some extreme cases the AOCI loss now exceeds total bank equity altogether. This puts a bank in a pickle. It is at the mercy of the highest marginal deposit costs in the marketplace, because it literally cannot afford to sell bonds to raise cash. Meet “liquidity risk”.

In the Savings and Loan Crisis, their effort to attract more deposits by offering higher interest rates resulted in higher cost liabilities that were not able to be covered by the lower interest rates at which they had loaned money. As a result, one-third of S&Ls became insolvent. We wonder what would happen if the regulators ever required financial institutions to adjust capital for market losses.

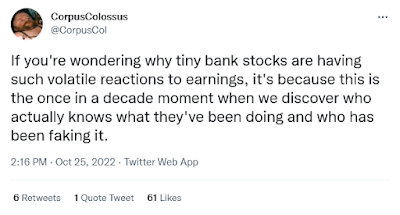

On Twitter is CorpusColossus (@CorpusCol), who really knows banks and had two terrific tweets on this subject:

We will be writing more about this in the upcoming Issue of the Oddball Stocks Newsletter.